The magazine’s Ethicist columnist on conditions parents attach to their wills.

Around a decade ago, my mom informed each of her children that she and my stepfather put a codicil in their wills disinheriting any of their children married to someone not recognized as Jewish by her local Orthodox Rabbinate.

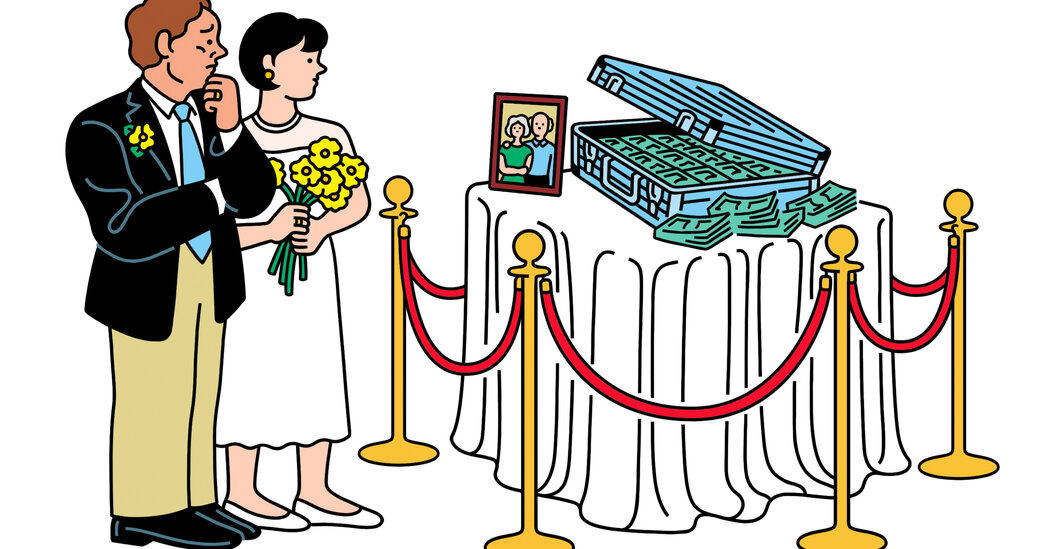

I believe a will is not just about money; it’s also an expression of values and love. I have strongly objected to this codicil, or more specifically, to her having informed us about it: The two are thereby using their wealth as an implicit weapon in service of their religious views.

She says I’m reading too much into it. She claims she informed us in the name of “transparency,” so we wouldn’t be surprised later, and that it’s her money to do with as she pleases, anyway — though she concedes that she also informed us in case it may influence decisions we make.

I’ve since married someone who fits her definition of a Jew, so the codicil doesn’t apply to me. Still, I have three middle-aged siblings who are all not religious and unmarried, and I think they remain so at least partially because they’re stuck, unable to both follow their hearts and avoid betraying my mother’s love — and its most powerful signifier, her will. Is she right to have the codicil? And to have told us about it? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

What your mother and her husband are planning to do, as it happens, is at odds with much rabbinical thought concerning inheritance. A Judaic scholar I conferred with confirms that the mainstream Talmudic tradition of Halakha, or Jewish law, revered by the Orthodox Union, holds that apostates don’t forfeit their right to inherit. (Maimonides would allow a rabbinical court to fine an apostate at its discretion — but the permission is not given to the parents.) And then marrying a non-Jew isn’t as severe a transgression as apostasy; so if an actual apostate retains the right to inherit, it’s clear that someone who has merely married a non-Jew does as well. You might think that it’s awkward to penalize your kids for departing from Halakha by departing from Halakha yourself. But picking and choosing from the traditions you are going to respect is a widespread practice among Jews and gentiles alike.

The real question is whether the scheme is wise or decent. I fear that it is neither. That your siblings now have an incentive to postpone marriage until your parents are dead raises doubts about its wisdom. That your siblings might marry someone acceptable to the Orthodox rabbinate in order to secure this inheritance raises doubts about its decency. Whom we marry is properly up to us. Parents may express their views; coercion, though, is wrong. Does threatening to deprive someone of a substantial inheritance amount to coercion? Different understandings of coercion will come out differently on this. But it’s too close for comfort.

You suggest that once your mother and stepfather decided not to leave money to a child who hadn’t married the right kind of Jew, it would have been better had they kept it to themselves. That’s an odd conclusion, but a cogent one: They should have restricted themselves to morally acceptable forms of suasion. In the meantime, you might encourage them to discuss their codicil with a rabbi, who could explain to them what the Jewish sages had to say on the subject.

Readers Respond

Last week’s question was from a reader who works at the same university as their husband and supports his career with unpaid editing help. They wrote: “Why shouldn’t I be compensated for my specialized contribution to his scholarship? For me, this is not an intellectual question; it has begun to make my blood boil. … Should I help him as a loving partner, or only do editing work for paying customers?”

In his response, the Ethicist noted: “I’m not sure marriage is the right arena to fight the many genuine inequities in the system of rewards you’ll find in the university, and in our larger society. … But you have no obligation to edit your husband’s papers, and you’ve come to experience it not as part of a mutually supportive relationship but as part of a larger pattern of exploitation. So you should feel free to bail. It isn’t really a gift if it makes you grit your teeth.” (Reread the full question and answer here.)

⬥

Your response to the wife/editor makes my blood boil! Women have been subtly (and overtly) coerced into doing this type of supportive, unpaid work for far too long. She only benefits from her husband’s success if they remain married. Her time, expertise and energy goes into supporting his career, and it’s highly likely that she also does more than half of the domestic duties. Societal pressure to be “good wives” and “helpmates” has kept women from flourishing throughout history. Time for that to end. — Anne

⬥

The letter to the ethicist, and his lukewarm response, illustrate a much deeper issue with our understanding of marriage. Should a spouse do unpaid work to support the partner whom they claim to love above all others? In a word, yes, and without counting the cost. This has literally nothing whatsoever to do with the numerous unfairnesses in contemporary academia. — James

⬥

Academia has a long history of male faculty benefiting from, and even depending on, the unpaid labor of their female partners. If the letter writer needs another reason to stop performing this unpaid work, consider the message that it sends to her husband’s trainees. The male postdocs are learning that they should expect a partner to do this editing work for them, and the female postdocs are learning that they will be expected to perform this free labor for their partners. — Beth

⬥

Why shouldn’t her name be added as one of the co-authors? I am a female scientist and agree that sector is dominated by men. What the letter writer is doing is very much necessary, yet under appreciated, much like background support has been over the years. I think adding her name to the list of co-authors would provide equivalent compensation and, more important, recognition of her efforts. — Maureen

⬥

As a former state university professor, I’ve witnessed time and again the exploitation of adjunct lecturers, and acknowledge that we benefited by the fact that they lightened our own teaching workload for pennies on the dollar. With that in mind, I recommend that you do your own work and let your husband do his. Editing one’s own papers is part of the writing process and therefore part of his job. Yes, working for tenure is grueling, but I don’t know anyone who used an editor. — Greta